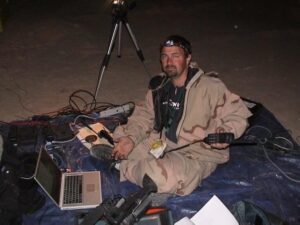

Jerry Simonson, JEM alum, on a recent trip to cover the war in Ukraine.

If you want to hear riveting tales of what it’s like to be a photojournalist covering breaking global news, Jerry Simonson (’91) has almost 30 years’ worth. Whether it’s about the time he grabbed exclusive footage of hostages during the Iraq war or the challenges of uploading video during the immediate aftermath of Hurricane Katrina, Simonson can recount highlights from his career as if they happened yesterday. He is still a senior photojournalist for CNN, so some of his stories are quite literally from yesterday.

“The exciting thing for me about journalism is being dropped in somewhere like Haiti and you have to figure out what’s going on and get right to work,” he said. “I don’t live a normal life, this is not a normal life at all. I leave every day and there’s a suitcase in my car and I say goodbye to my wife; and I may be back in a month, I may be back that night. It’s not for everybody, but for me, that’s where it’s at.”

Simonson got his first taste of broadcast journalism at Alcoa High School, which had a small broadcasting department that taught him camera work. That led him to exploring what the University of Tennessee, Knoxville, had to offer; when he saw the broadcasting set-up that now-retired School of Journalism and Electronic Media Professor Sam Swan had set up, he decided UT was the right choice.

As a student, Simonson chased every hands-on work opportunity he could. Among those were an internship with WBIR- TV on The Heartland Series (a creative documentary project) and shooting footage for UT Athletics. One of his best pieces of advice to any current College of Communication and Information student is to pursue every chance they have to do real-world work before graduating.

“Go to your classes, make good grades, but try to plug yourself in anywhere to get that experience—find people doing the work you want to do, and tap into them,” he said. “Do an internship your sophomore, junior, and senior year; find somebody out there in the real world and shadow them and get that experience.”

Simonson credits his own tendency to be “bullish” for landing him an internship and subsequent full-time position at CNN in Atlanta. He went to drop off his resume and was quickly told that they receive thousands of such resumes a month—that’s when he called upon the Volunteer network and had current senior director of VFL Films Barry Rice get in touch with a sports producer at CNN named Bill Galvin, who in turn connected Simonson with the person who ran the internships program at the network. He had an internship there by the next day, which he worked at without pay for eight months until they hired him into the video journalist program.

He put in his dues ripping scripts (a term used to describe the process of taking scripts off the printer, collating them, and distributing them to various people on the broadcasting team), dealing with the teleprompter, and floor directing. Doing the grunt work paid off in more ways than one: he actually met his wife 30 years ago at the teleprompter controls, and he was eventually promoted to an editor position. But Simonson knew where he belonged, and his editing job brought that to the forefront of his mind.

“When I was editing, I was taking in a lot of feeds from places like Bosnia, and I was jonesing to get into the field. But my boss said, ‘You got to wait.’,” he recounted. “Then the Oklahoma bombing happened in ’95, and when that happened, my boss said, ‘Can you get on a plane in two hours?’ and I said yeah. I was there for two weeks.”

While covering the bombing, Simonson made connections with the Miami CNN bureau, which led to him getting a job there in 1996 as a sound tech and editor. That’s when his trips across the country and the world began, and he found himself in many different places and scenarios that are unique to the job.

“I do a little bit of everything. I went back to Iraq in 2007, to Haiti after the earthquake in 2010, and I just recently went to Poland and Ukraine back in the spring for the war. I’ve done entertainment, sports, everything from the locker room for the Stanley Cup, to the World Series, Super Bowls, a little bit of everything. I just covered the hurricane in Florida, and I’ve probably done 50-60 hurricanes,” he said. “I don’t think it’s for everybody, but it’s somewhat addicting; when anything big happens, there’s a certain group of people who end up there, and you want to be there, no matter the difficulties.”

Not only has Simonson weathered literal storms in the course of his work, but he’s also always acclimating to the fast-changing technology that is a required part of being a broadcast journalist. Gone are the days of sitting under a truck in Iraq for an entire night using two satellite dishes with a 256K modem and losing connection repeatedly until his footage finally uploaded—now he can use LiveU technology that combines six SIM cards to link into the cellular system and provide a broadcast-quality signal. Technology may make some things easier, but it also demands more skill-learning and expectations of even faster turnaround, he noted.

Even though a lot has changed over the years, Simonson said the core tenets of journalism have always stayed the same. He’s excited about all the opportunities this next generation of journalists have at their fingertips, with new platforms and tech, but said students and new graduates need to keep in mind that a strong foundation will carry you through a journalism career.

“It doesn’t matter what camera or what platform or streaming service you have, you have to be a good storyteller and put the story together in a way that is compelling. If you don’t know the fundamentals, you’re not going to win the game,” he said.